TAIICHI OHNO

Av Patrik Öhman

Taiichi Ohno (1912 – 1990) anses vara fadern till Toyota Production System (TPS) och därmed en enormt inflytelserik personlighet under den japanska efterkrigsindustrins renässans.

Ohno är född i Dalian, östra Kina, 1912 och han tog examen från Nagoya Technical High School som maskiningenjör innan han anslöt sig till Toyota 1932. Han arbetade initialt i Toyota Spinning och Weaving. Han förflyttades till Toyota Motor Company 1943 vid en tidpunkt då Toyotas produktivitet var långt under den amerikanska Detroit-baserade motorindustrin och gjorde där karriär upp till ledningsnivå. Ohno trädde fram under TPS formativa år (ungefär 1945- 1965 när Toyota kämpade för att överleva). Toyotas dåvarande vd Toyoda Kiichiro, deklarerade en utmanande målsättning samma dag som andra världskriget slutade:

“Catch up with America in three years. Otherwise, the automobile industry of Japan will not survive“.

(Ohno 1988 s. 3)

Toyota stod på randen till konkurs under stora delar av denna period och hade inte råd med massiva investeringar i ny utrustning eller lager. Trots dessa hinder introducerade Ohnos ledarskap ett nytt sätt att tänka och en ny arbetskultur i företaget. Han menade att det enda skälet till att Toyotas produktivitet var lägre än hos deras amerikanska konkurrenter var ineffektivitet och slöseri. Efter att ha blivit utsedd till direktör 1954 steg han igenom alla ledningsskikt i företaget tills han blev vice vd 1975. I början av 1980-talet gick Ohno från Toyota och blev president för Toyota Gosei, ett Toyota-dotterbolag och leverantör. Han dog i Toyota City 1990.

Hur Ohno och Toyota beskrivs i “The Machine…”

Berättelsen om Toyotas utveckling och överlägsenhet över sina massproducerande konkurrenter blev först uppmärksammat på bred front i Europa och USA genom boken “The Machine That Changed the World” (Womack, Jones och Roos 2007, först publicerad 1990). Denna boks framgång genererade stor uppmärksamhet åt att finna:

“a better way to organize and manage customer relations, the supply chain, product development, and production operations“.

(Womack och Jones 1996 s. 9)

Den dokumenterade ledningsfilosofins utveckling inom bilindustrin, från de tidiga hantverksproducenterna, till massproduktionsteknikerna som exemplifierades av Ford / GM. Innan de berättade historien om TPS: s utveckling (cirka 1945-65) och den tillhörande berättelsen om Toyotas “produktionsgeni’” Ohno (se Womack m fl 2007 s. 48). Ohno hade genom nödvändighet utvecklat ett kontrasterande tillvägagångssätt för produktion jämfört med de amerikanska bilföretagens massproduktion. Konkurrensfördelar kunde inte uppnås av Toyota genom att försöka imitera de amerikanska jättarnas jakt på stordrift.

Genom att experimentera med enklare pressverktygsskiften (som pressar metallplåtar) kunde Ohno förfina en hel process tills tiden kunde reduceras från att ta en dag till 3 minuter. Därmed gjorde han den första av en serie kontra-intuitiva upptäckter: det kostar mindre per del att göra små satser av pressad plåt än att producera i stora satser. Ohno försökte förstå mer om varför färre enheter och större variation ledde till lägre omkostnader. Han fann att den sanna tillverkningskostnaden låg i flödet från start till slut. Större variation i produktionslinjen lämnade färre delar uppbundna i lager och pågående arbete. Samtidigt som enhetskostnaden för varje produkt var högre, var de totala produktionskostnaderna betydligt lägre (Womack et al 2007 s. 52). Som Ohno uttryckte det:

“To think that mass-produced items are cheaper per unit is understandable, but wrong“.

(Ohno 1988 s. 68)

Ohno förstod med tiden att flödesekonomi var överlägsen skalekonomi. För att se detta flöde, behövde han förstå sin organisation som ett system.

En supermarket som inspiration

Ohno var känd för att laborera med utrustning och maskiner för att producera föremål i tid. Men han fick ett helt nytt perspektiv på “just-in-time” -produktion när han besökte USA 1956. Ohno åkte till USA för att besöka bilfabriker, men han var mest imponerad av de amerikanska supermarkets som han hade studerat sedan sent 1940-tal (Ohno 1988 s. 26). Japan hade inte många självbetjäningsbutiker än, så Ohno förundrades över att kunderna valde exakt vad de ville ha och i de kvantiteter som de behövde.

Ohno beskrev ofta sitt produktionssystem i termer liknande en supermarket. Varje produktionslinje anpassade sin varierande output så att efterföljande linje kunde välja, liksom varor på en butikshylla. Varje linje blev kunden för den föregående linjen. Och varje linje blev en supermarket för efterföljande linje. Följande linje valde de objekt som behövdes och bara de objekten. Den föregående linjen skulle producera endast ersättningsobjekten för de som den följande raden hade valt.

Detta format var ett “pull”-system som drivs av efterföljande linjers behov. Den stod i kontrast till konventionella “push”-system, som drivs av outputen från föregående linjer. Ohno utvecklade ett antal verktyg för att driva sitt produktionsformat i en systematisk ram. Det mest kända av dessa verktyg är kanban-systemet, vilket möjliggör överföring av information i och mellan processer på instruktionskort.

TPS utvecklades för att överleva

I slutet av sitt liv frågades Ohno av en journalist från “The Economist” varför TPS hade utvecklats. På ett karaktäristiskt uppriktigt sätt svarade han att TPS var “last fart of the ferret” (tydligen avger en iller en kraftfull lukt när den är trängd, liknande en skunk). TPS utveckling i motgång mognade till ett strukturerat systematiskt svar på alla utmaningar som Toyota mötte efter 1945. Samtidigt förändrades den interna och externa miljön (strejker, Koreakriget, oljekriser) för Toyota. Ohnos tillvägagångssätt rubbades aldrig trots utmaningarna: hans fokuserade alltid på att eliminera slöseri och förbättra systemet. I slutet av hans liv, fick Ohno frågan, “Vad gör Toyota nu?” Han svarade:

“All we are doing is looking at the time line,’ he said, ‘from the moment the customer gives us an order to the point when we collect the cash. And we are reducing that time line by removing the non-value adding wastes“.

(Ohno 1988 pix)

Ohnos ledarskap

Ohnos ledarskap beskrivs som att han satte människor först och främst i företaget, i stället för de konventionella antagandena att företag är mekanismer som behöver kapital, genererar kostnader och attraherar intäkter. Han var radikal i bemärkelsen att maskiner och system skulle tjäna människor, deras mästare, snarare än tvärtom.

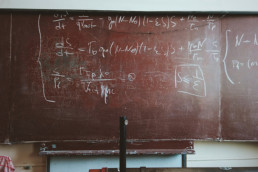

Figur 2 Ohno’s Method (Nakane och Hall 2002)

Ohnos favoritord var “förståelse”, vilket betyder “to approach an objective positively and comprehend its nature” (Ohno 1988 s. 57). Hans metod utvecklades som ett sätt att uppnå en sådan förståelse av sitt arbete som ett system. Ohno beskrev företag som systemiska och liknande den mänskliga kroppen där nerverna: “cause us to salivate when we see tasty food” (Ohno 1988 s. 57).

Insikten om en organisations systemiska karaktär ledde honom till att försöka anpassa TPS som ett ekvivalent nervsystem, svara på yttre stimuli genom att “göra bedömningar autonomt på lägsta möjliga nivå”. Han betonade att:

“Management’s role is leadership, developing all the people to autonomously work toward common ends“.

Han förespråkade dessutom att alla borde “strive for a targeted ideal system“, men att man skulle ha i åtanke att förutsättningar förändras och att “all systems are transient, so people and systems must be flexible and adaptive, not just optimal“.

Ohnos metod leder till att man organiserar för medarbetare och processflöden, problemfokus och problemlösning, snarare än för kontroll. Närhet till den direkta åtgärden är ett krav för supportarbetarna och cheferna, så att interna processer kan kopplas tillbaka till kundens perspektiv. Nakane och Hall jämför Toyotas arbetssätt med vad en militär organisation kallar “readiness“: utveckling av första linjens medarbetare att hantera och förbättra processerna autonomt, så att allas bidrag maximeras inom paraplyorganisationen. Detta gör att organisationen kan vara utmärkt enligt konventionella mått mätt, men samtidigt behålla förmågan att vara flexibel vid behov.

Ohno förstod att Toyota Production System bara var just det – ett system; Missförståelse av den utgångspunkten leder många till att misslyckas med att förstå vad som utan tvekan är en betydande möjlighet att lära och förbättra. Ohno bör därför betraktas utifrån en systemisk tradition, som ser hur en organisations delar interagerar för att producera helheten och som ständigt söker efter feedback om hur de presterar. Det är först när systemperspektivet förstås som organisationer kan realisera deras potential att prestera liksom Toyota.

‘Ohno-san never explained’

Ohno vara en besvärlig karaktär. Han beskrevs som en “praktisk coach” i motsats till en konsult eller professor och han var inte en vanlig chef. Han föredrog en roll nära arbetet och ogillade kontoret. Ohno mötte regelbundet motstånd när han först satte sig för att övertyga företaget om att radikalt ändra sina tillverkningsprocesser. Det sägs att det tog Ohno 25 år att sprida innovationerna hos TPS genom hela Toyota och dess underleverantörer. Även i fabriken där han var chef, tog det enligt honom ungefär 8 år för att äntligen få saker att flyta. Arbetarna var inte samarbetsvilliga med vad de kallade hans “fåniga” förändringar. Ryktet sa att det stönades och man sa “Oh no, here comes Mr Moustache!” När de såg honom (Hutzinger 2008).

Ohno hade rykte för att skapa rädsla hos andra. John Bicheno vid University of Buckingham säger att:

“there are still some older Japanese that worked with Ohno – and virtually all who have worked with these guys say that they give orders, are highly critical, and expect it to be done“.

Michikazu Tanaka gav denna redogörelse för Ohnos fasta men rättvisa förhållningssätt till lärande på arbetsplatsen (från Fujimoto och Shimokawa eds 2009 s. 49):

“No one ever got a scolding from Ohno-san for getting something wrong as long as they were doing their best. But he’d turn red in the face and deliver a severe tongue-lashing to someone who was slacking and made excuses for messing something up… The way to pass this spirit (of Gemba gembutsu: going to see problems first-hand) on to the next generation is to go out into the workplace and scold people. If someone screws up, take them into the workplace, show them exactly what’s gone wrong, and give them a good scolding. When someone gets a scolding in the workplace while looking at what’s actually happened, they can’t make any excuses. The scolding presents the person with a higher standard to meet. On the other hand, you can’t be strict all the time. Ohno-san cautioned me one time after I’d been scolding people in the workplace. “You need to be careful not to discourage people who already have the right motivation.” I asked him what he meant, and he replied, “Motivated people want to do things, even when they think they can’t. And some things really are impossible for some people. At times like that, motivated people can get discouraged. So even if you say something strict, you also want to find an opportunity to extend a helping hand.

Extending a helping hand lets people know that you value their effort, even if they were unsuccessful. [Managers] who never extend a helping hand can never earn the trust of their subordinates. We need to accompany strictness with a readiness to help. And to do that, we need to know what’s going on in the workplace. If you don’t know what’s happening in the workplace, you can’t do anything for the people there. Managers who are happy when problems stop showing up and operating rates rise are no good. Managers need to let their people know that they’re happy to see problems show up. Ordinary people tend to want to hide problems. We shouldn’t ever think badly of people who reveal one problem after another. We should welcome situations where problems become clear“.

Ohnos aptit för att driva ut slöseri från Toyota-systemet var hänsynslöst. Det finns en historia (se Norman Bodek-intervju, n.d.) att en dag Ohno gick in i ett av de stora lagren och sa till cheferna runt honom:

“Get rid of this warehouse and in one year I will come back and look! I want to see this warehouse made into a machine shop and I want to see everyone trained as machinists“.

När han återvände ett år senare hade byggnaden blivit en verkstad. Ohno hade inte sagt åt dem hur man skulle göra det. I stället krävde han bara att de gjorde det. Som Tanaka sa:

“Ohno-san never explained his reasons, so the only way to learn was by doing“.

(Fujimoto och Shimokawa eds 2009 s. 57)

På senare år blev han en mentor till Toyotas TPS-ledare en-mot-en eller i små grupper, skickade han ut dem för att studera verkligheten, förstå den noggrant och i sin tur utveckla handledare och medarbetare för att förbättra processerna omkring sig själva (Nakane och Hall 2002). Alla Ohnos studenter minns att de hade känslan av att ha bemästrat TPS, för att därefter ha fått en ny skarp frågeställning och skickats ut för att lära sig mer. Det har sagts att nära slutet av sin karriär hade hans sätt varit så utmanande att det fick Toyota till att hövligt flyttas till en roll som direktör i ett dotterbolag.

Råd till chefer: gå och se!

Michikazu Tanaka var produktionschef på Daihatsu, ett annat japanskt bilföretag som arbetade nära Toyota i 1960-talet (från Fujimoto och Shimokawa eds 2009). Tanaka talar varmt och med uppenbar vördnad för sin mentor:

“Gemba gembutsu [also genchi gembutsu: a commitment to seeing things (gembutsu) firsthand as they really are in the workplace (gemba or genchi)] was absolutely fundamental to Ohno-san’s approach. He never rendered judgment simply on the basis of hearing about something. He always insisted on going to the place in question and having a look. On occasions when we might press him for an opinion, he’d say, “You’re the one who has seen the thing. You know better than I do. How could I talk about something that I haven’t seen?”

(Ohno would assign individuals from Toyota to assist Daihatsu with their kaizen. On one occasion, he assigned a Toyota production engineer to help with some automation kaizen. Tanaka wondered how it would help them.)

…for a week he did nothing at all. He simply watched what was happening in the workplace. On the Monday of his second week at our plant, he came by my desk and described his impressions and his plans as follows.

“I watched the activity in your workplace carefully for a week, and I saw that people are working extremely well. I struggled to think of something that I could do for you, and my conclusion was that I have no role to play here.

I stopped by Ohno-san’s house on the way home Friday evening and told him what I have just told you. He said, ‘Your problem is that you’re trying to think of something to teach the people at Daihatsu. You don’t need to teach them anything. What you need to do there is help make the work easier for the operators. That’s your job.”

… Ohno: “When you go out into the workplace, you should be looking for things that you can do for your people there. You’ve got no business in the workplace if you’re just there to be there. You’ve got to be looking for changes you can make for the benefit of the people who are working there“.

Hitta och eliminera slöseri

“Here’s an example of Ohno-san’s approach. He was observing the work on an engine assembly line one time when he was a plant manager, and he noticed that one of the workers needed to lift a heavy engine block once during each work cycle. Ohno-san wondered why that was necessary. He called the production chief over and ordered him to go find out what was going on. The production chief came back and reported that the roller conveyor was broken.

“What in the world do you think you’re doing here?” shouted Ohno-san. “We don’t hire people to lift engine blocks. You go check and see right now if you’re not sitting on other problems just like this one.” The production chief soon reported three similar problems, and he received the predictable scolding from Ohno-san. “You’re out here on the floor every day, but you’re not really seeing anything: whether your people are having problems with something, whether waste is happening, whether you have overburden somewhere.”

Ohno-san insisted that only about half of the activity in a typical workplace was value-added work. The rest was just spinning wheels, not making any money for the company. He taught us to see. I took a fresh look at the workplace, and I could see that he was right, that waste was happening everywhere”.

Högsta ledningens åtagande

“When Ohno-san gave guidance to companies, he always started with the president. ‘All the training in the world will come to nothing unless senior management displays a strong commitment. If you demonstrate the right commitment, I’ll provide your people with the training they need“.

Skriftliga rapporter är inget substitut för kunskap

“Ohno-san hated written materials. If you took him some papers to see, he might go through the motions of looking at them, but he wouldn’t really pay any attention at all. You’d be trying to explain something in the documents, and you could tell from his eye movements that he couldn’t care less. When you got done, he’d hand the papers right back to you. He’d give really detailed instructions in the workplace, but he almost never had anything to say in response to written reports. I never saw any papers on Ohno-san’s desk. That’s no exaggeration. Literally, no papers at all. The only documents I ever saw him pay any attention to were the factual records of production and sales results: things like how many vehicles we sold yesterday, how many vehicles our plants produced yesterday, what the operating rates were, and so on. Those numbers were records of actual results, so they were indisputable facts. Ohno-san had no interest in any other written materials. He only trusted things that he could confirm with his own eyes.

I visited Ohno-san one time at Toyoda Boshoku (Toyoda Spinning and Weaving) when he was the chairman there. He was in a foul mood and promptly let me know why.

‘Some guys in charge of kaizen at Toyota were just here. They said they were going to hold a jamboree to introduce case studies and that they wanted me to come. I got angry and told them that kaizen is about eliminating waste. I asked why they would hold a kaizen event that entailed the waste of preparing a lot of useless materials. People can see the kaizen in the workplace. I told them that they didn’t have a clue. Their job is to eliminate waste, and they’re the ones creating waste.’

The group responsible for kaizen at our company came to me sometime after that encounter with Ohno-san and asked for some materials. I refused and told them how angry Ohno-san would be at such a request. They insisted that they needed to make a report about the kaizen activities.

I asked why they needed to make a report when people could see the actual kaizen in the workplace. I told them to show people the kaizen in practice. We have too many people these days who don’t understand the workplace. They’ve got that tinfoil over their eyes. They think a lot, but they don’t see. I urge you to make a special effort to see what’s happening in the workplace. That’s where the facts are. And the truth is hidden in the facts. Our job is to get a handle on the truth”.

Utvärdera personer

“The way you evaluate people shapes their behaviour. Production at the Takaoka Plant slumped one time [on account of weak demand], and the plant was operating only half days. At times like that, the people should simply take the rest of the day off. But when I went to the workplace, I found the lights on and people sweeping up and getting ready for the next shift. I noted that they were wasting electricity and asked what they were doing. They answered that their evaluations would suffer if they weren’t doing something that looked like work all the time. When you’ve got idiots for managers, people in the workplace end up wasting money“.

Referenser

Intervju med Norman Bodek nedladdad från http://www.strategosinc.com/nbodek.htm – 20150207

Huntzinger J presentation at TWI Summit, May 2008 http://twisummit.com/twisummit_old_page/TWI-Ohno%27s%20Vehicle%20to%20TPS%20-%20TWI%20Summit%202008.pdf – nedladdad 20150307

Nakane och Hall 2002 ‘Ohno’s method: Creating a survival work culture’ Target magazine vol 18, no 1 http://www.ame.org/sites/default/files/target_articles/02-18-1-Ohnos_Method.pdf – nedladdad 20150207

Ohno, Taiichi 1988 ‘Toyota Production System’ Productivity Press: Portland, Oregon

Shimokawa K och Fujimoto T eds 2009 ‘The Birth of Lean: Conversations with Taiichi Ohno, Eiji Toyoda, and other figures who shaped Toyota management’ The Lean Enterprise Institute: Cambridge, Massachussetts

Womack J, Jones D, Roos D, (2007) “The Machine That Changed the World” Simon and Schuster: London. Först utgiven 1990.

Womack, J. P. och D. T. Jones 1996 ‘Lean Thinking’ Simon & Schuster: New York